Volume 1, Issue 1, January–February 1964 Volume 1, Issue 2, March–April 1964 Volume 1, Issue 3, May–June 1964 Volume 1, Issue 4, July-August 1964 Volume 1, Issue 5, September–October 1964 Volume 1, Issue 6, November–December 1964 Volume 2, Issue 1, January–February 1965 Volume 2, Issue 2, March–April 1965 Volume 2, Issue 3, May–June 1965 Volume 2, Issue 4, July–August 1965 Volume 2, Issue 5, September–October 1965 Volume 2, Issue 6, November–December 1965 Volume 3, Issue 1, January–February 1966 Volume 3, Issue 2, March–April 1966 Volume 3, Issue 3, May–June 1966 Volume 3, Issue 4, July–August 1966 Volume 3, Issue 5, September–October 1966 Volume 3, Issue 6, November–December 1966 Volume 4, Issue 1, January–February 1967 Volume 4, Issue 2, March–April 1967 Volume 4, Issue 3, May–June 1967 Volume 4, Issue 4, July–August 1967

Transcription of The Best of Fact's introduction by Warren Boroson, 1967*

This magazine is dedicated to the proposition that a great magazine, in its quest for truth, will dare to defy not only Convention, not only Big Business, not only the Church and the State, but also—if necessary—its readers.**

According to a few rumors that have been floating around, Fact Magazine was bankrolled at a meeting between Adam Clayton Powell, Jimmy Hoffa, Tim Leary, Elizabeth Taylor, and Fu Manchu in an LSD session at THRUSH headquarters in Passaic, New Jersey.

According to Ralph Ginzburg, however, the man who began the magazine, Fact is the Son of Eros—an assertion that may be slightly closer to the truth.

In 1961, the U.S. Postal Service, in its finite wisdom, concluded that Eros, the first magazine that Mr. Ginzburg published, was obscene and could not be sent through the mails. Only Volume 1, Number 4, which contained photographs of a white woman and a Negro man together, unclothed, was singled out for this attention, so he could of course have gone right ahead and published Volume 2, Number 1, which was already at the printer’s. But Mr. Ginzburg’s lawyers warned him that if Post Office censor-morons were to be kept at bay, all further issues of Eros would have to be about as ballsy as Godey’s Lady’s Book. After due reflection, he decided to stop publishing Eros, confidently awaiting victory in the courts.

Meanwhile, Eros still had a staff of eager workers, a floor of offices near the New York Public Library, and a large number of subscribers who were wondering where their magazine was. Now, for many years Mr. Ginzburg had been thinking of launching another publication, a magazine of dissent, a magazine that would print those articles other magazines are too timid, or too corrupt, to print. Thanks the the U.S. Post Office, here was his opportunity. So in late 1962, he and I began sending out brochures for a new muckraking magazine; money flowed in; with the money, Fact was born.

—

One of the assumptions behind the magazine was that advertising overtly and covertly castrates content. Therefore, Fact would take no advertising. We wanted to be perfectly free to rough up powerful and sacrosanct institutions when they deserved roughing up, and free to explore topics considered taboo by most other magazines and the big advertisers that support them.

A second assumption was that Fact would be a professional magazine, one that profited from the skills of modern journalism. Manuscripts, if unclear, would be made clear—“translated into English,” as H.L. Mencken used to say. Formless, discursive manuscripts, would be organized, preferably around one central theme. Manuscripts written ploddingly would be brightened up and tightened up.

A third assumption was that Fact would be a magazine, a storehouse, and not just a house organ for anyone’s pet ideas. Articles in Fact, if they were responsible and cogent enough, did not have to coincide with the views of the editors. To be sure, Fact would have a “personality”: It would be tough-minded, rationalistic, progressive, and psychologically oriented. But it would not preach political liberalism and practice intellectual totalitarianism.

Finally, there was the assumption embedded in the name itself. It was called Fact because the magazine would concentrate on articles grounded in personal experiences and scientific research. Most people’s opinions, the editors believe, are the products of their personalities—their emotional needs and desires. To a degree, this makes their opinions suspect. In Fact, we hoped, all opinions expressed would be corroborated not only by independent research, but by personal, experiential familiarity with the subject. The ivory-tower “expert” would be regarded with a little skepticism: There always seems to be a professor of astronomy at Harvard who is convinced that the world is flat. Our expert would be a man who had not only read the leading works on (say) employment agencies, and who had not only sought out the views of insulated experts, but had also actually worked for an employment agency. Furthermore, by personalizing articles in this way, we could do what every new magazine, and every new art movement, should do: get closer to current, everyday reality.

In sum, we wanted Fact to have the lucidity of the Reader’s Digest, the cleverness and wit of Time, the intrepidity of the old American Mercury, the integrity of the New Yorker, and the factual foundation of Scientific American.

—

The topics Fact would cover, and has covered, are almost unlimited—from Mad Magazine to Warren Gamaliel Harding’s alleged Negro ancestry. Yet Fact’s articles are linked, on the one hand, by a critical, personal, and psychological approach, and on the other by the fact that other magazines usually shy away from such articles—because the topics may be depressing (like the examination of life on Welfare), emotionally charged (like miscegenation), fiercely controversial (like the campaign to tax churches), or deeply disquieting (like the mental condition of Presidents and would-be Presidents). Most American magazines, emulating the Reader’s Digest, wallow in sugar and everything nice; Fact has had the spice almost all to itself.

Although it was not deliberate, Fact’s articles have come to revolve around certain themes, themes that may represent key problems faced by this country in the 1960s.

First and foremost is America’s obsessive and paranoid anti-communism. Communism, like all forms of totalitarianism, should be condemned and opposed, just as the United States should condemn and oppose all totalitarianism regimes—in Haiti, South Africa, Rhodesia, Spain, Portugal, and Mississippi. That a totalitarian regime happens to be communist doesn’t make it any worse. And just as we manage to get along with Haiti and South Africa, we must learn to live with China, Cuba, and a communistic Vietnam. For if a country like Vietnam voluntarily casts its lot against us, we must accept that decision—and learn the bitter lesson that our support of dictators like Diem, and now Ky, is self-defeating. Today the survival of civilization seems less endangered by communism’s purported aggressiveness than by our own bellicose, paranoid anti-communism. Fact has been trying to explore the underlying reasons behind this obsession, and more important, trying to transform Anti-Communism into plain, ordinary anti-communism.

A second theme is also not new: briefly, it is our neglect of the public sector of our economy—our cities, schools, hospitals; and especially our neglect of “deprived institutions”—prisons, mental hospitals, welfare departments—the victims of which are inarticulate and their sufferings little publicized. We are, true enough, making headway: Today there is serious talk, for example, of a negative income tax. But when are we going to place the public welfare above such goals as reaching the moon, or being able to kill everyone on earth a few dozen times?

And then there is what A.J. Liebling called the Press Mess. American journalism, like American medicine, is the best in the world, and it is very bad. Our newspapers, magazines, and TV stations are afraid of advertisers, afraid of pressure groups, afraid of controversy. But their timidity is a minor fault compared with their corruption. The great contribution America has made to mass communications is impartiality, the objective reporting of notable events. Yet this ideal is being flagrantly violated right and left, especially right, and principally by two of this country’s leading magazines. One is the Reader’s Digest, which piously claims to be impartial but in reality deals a stacked deck; the other is Time Magazine, which reports the news at the same time that it colors the news. To Time. “Interpretive” reporting means interpreting it your way. When the fear of Henry Luce’s empire finally abates, he will be remembered as the man who dirtied the mainstream of American journalism.

A fourth theme of many Fact articles concerns the need for more and strong countervailing powers in American society, especially to protect the weak, naïve consumer against predatory producers. The poor American consumer may drive a car that is unsafe, take drugs whose pernicious side-effects he is unaware of, buy insurance that gives him shoddy coverage, get a job though an employment agency that charges excessively, patronize travel agencies that don’t tell him what he is paying for, and smoke cigarettes because he wasn’t warned soon enough and forcefully enough about the harm smoking causes. As for reforms, the produces themselves sing the refrain, “I’d rather do it myself.” They haven’t, they won’t, they can’t. We need, therefore, strong outside agencies to fight for the average American citizen—agencies that will police TV stations, advertisers, drug companies, utilities, and, of course, police the police.

And yes, we confess it: Another Fact theme has been sex, or better, taboo topics in general. Sex is taboo perhaps because the subject automatically arouses neurotic worries; or it arouses guilt and shame associated with almost-forgotten fantasies, impulses, and deeds; or just because of the common confusion of reproduction with excretion. Whatever the causes, anti-sexuality seems to be one of the most widespread neuroses in American society. After all, it cuts across party lines: You can be a political liberal, like I.F. Stone, and at the same time be a sexual Fascist. We probably need new classifications, like Up for the sexually enlightened and Down for the sexually repressed. But the real tragedy is that anti-sexuality creates misery and unhappiness not only for the afflicted, but for innocent bystanders—the women who want legal abortions, the youngsters who should have proper sex educations, and the writers, artists, and publishers who want to treat the subject honestly and responsibly.

One last theme I will mention is psychology. Perhaps Fact’s most pressing campaign has been to have the leaders of our country, and eventually of other countries, periodically examined by psychiatrists, as a step toward preventing future Hitlers and Stalins. But we have also attempted to use the insights of psychology, psychiatry, and psychoanalysis to understand and cope with various problems and puzzles of our civilization, from the rumors about Kennedy’s assassination to the revulsion commonly inspired by the thought of miscegenation, from the effects of circumcision to the irrational reasons behind America’s foreign policy.

—

Fact has had many things going for it. We have had, of course, the freedom to write about any subject at all, frankly and fully. Thus we were the first major magazine to publicize the scandalous hazards of American cars—in 1964, in an article researched by a then-unknown Ralph Nader. We were the first major magazine to warn that the Ku Klux Klan was riding again—again in 1964. Our exposé of the inhuman conditions at Bellevue Psychiatric Hospital in 1966 had something to do with the speeding of emergency financial assistance ti the hospital. Our first issue, in January-February of 1964, featured a first-person account on the effects of LSD.

We have had other, more subtle advantages, too. We publish about nine articles every 2 months, and therefore have been able to pick and choose. By and large, Fact has avoided the superficial, ephemeral articles that The New York Times Magazine, for example, is cursed with, and has probed the root causes of long-lasting controversies. Thus this book could easily have been doubled in size simply because Fact articles do not date readily.

Another advantage is that our staff is young and has the enthusiasm and the imagination of youth, and our staff is small, so we don’t suffer from the committee decisions that kill all projects except the most bland and seemingly safe. The average age of Fact’s editors is about 33. The aver age of editors of the Reader’s Digest, I would guess, is 82. Among Fact’s editorial innovations: the periodic study of recent joke-patterns as an indication of what the public may be really thinking; occasional symposia of well-known people’s opinions on some controversial issue, symposia that usually confirm that, indeed, personality forms opinions; and the publishing of wildly illogical, fiercely emotional letters to the editor, instead of only the more erudite, restrained ones, again as a way of getting Fact closer to the world as it really is.

—

The circulation of Fact, in 3 years, has zoomed to 250,000, easily surpassing the circulations of such established periodicals as the New Republic, the Progressive, the Nation, Ramparts, Evergreen Review, and a host of others. Among the authors who have written for us are Arnold J. Toynbee, Bertrand Russell, Mary Hemingway, Irwin Shaw, Sen. Ernest Gruening, Kenneth Rexroth, and Dr. Benjamin Spock. The Nobel Prize-winning biologist Hermann J. Muller has said that Fact is filling a needed role, and filling it well. Han Saying has praised Fact’s “courage.” Bertrand Russell has said that Fact is “well-prepared, irreverent, and serious.” The Rev. William Glenesk has written: “Yours is the toughest meat in print since Upton Sinclair’s Jungle or even the sharp pen of Jonathan Swift.”

We must be doing something right.

We do things wrong, too. But perhaps not as wrong as some of our critics think. Fact has been called sensational—and, in a sense, it is. We publish articles about miscegenation, the pathologic personalities of nuns and priests, the opinions psychiatrists have about a Presidential candidate who had two nervous breakdowns, the teratology of drugs purchased in supermarkets. We offer a forum to such cultural non heroes as Stokely Carmichael, a dead communist named Robert Thompson, the leader of the Society for Sexual Freedom, and assorted John Birchites. Of course Fact is sensational. So were the muckracking magazines of the early 1900s.

Many of our critics seem to be people who think in clichés. A new magazine that treats sex and other taboo subjects frankly, that skins fat cats and scalps big-wigs, that stirs up trouble—well, it must be out for a fast buck, or it must be full of falsehoods, or it must be communist-inspired. The one thing that many of Fact’s critics seem to have in common is that they haven’t read Fact Magazine very carefully.

But the longer any magazine exists, the more likely it will receive proper consideration. The same is true of individuals. In his young manhood, when Frank Lloyd Wright ran away with someone else’s wife, he was a pariah. Decades later, when his hair had turned white and his architecture was at last being appreciated, he became a Grand Old Man. Even with time, Fact will never become part of the Establishment, but someday it may get a better press. The New York Post may list its embargo on the mention of Fact’s name, The New York Times may write objective stories about us, and even Time Magazine—no, I almost got carried away.

This hostility is the burden of being a troublemaker. Orrin E. Klapp, professor of sociology at San Diego State College, points out in Heroes, Villains, and Fools that most Americans condemn five types of “villains”: the flouter, the rogue, the rebel, the outlaw, and the troublemaker. The trouble-maker’s “typical mischiefs,” Professor Klapp writes, “are to arouse discontent and conflict, disturb status, ‘rock the boat,’ and make a nuisance of himself… He is the opposite of the smoothie and good Joe, doing the very things they would avoid.” Whereas Americans seem to have conflicting feelings about flouters, rogues, outlaws, and rebels, they are virtually unanimous in their dislike of troublemakers. After all, it is painful to have to doubt and re-think one’s cherished opinions and one’s comfortable view of the world.

—

Fact owes a good deal of gratitude to many people. To its readers, of course. (Someone once sent us a letter saying, simply, “I appreciate what you are doing.” Enclosed was a check for $500.) To Sloan Wilson, not only for the many fine articles he has favored us with, but for his unflagging encouragement and enthusiasm. And, naturally, to the employees—past and present—who have worked so hard: Iswar Subramanya, Rita Bring, Miriam Fier, Paul Feingold, Marie Uddgren Sutton, Rufus Causer, Norman Moskowitz, Suzanne Aimes, Linda Broder, Barbara Quinn Smukler, Betty Feist, Arthur Whitman, Robert E. Lee, Henry Cojulun, Rosemary Latimore, Myra Shomer, John Dempsey, and Sandy Russo.

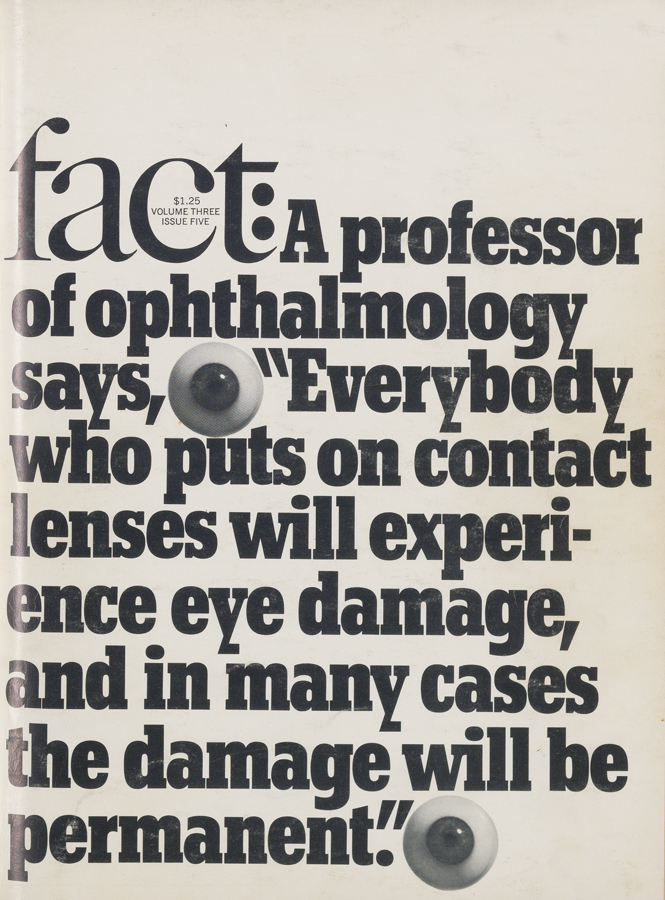

Finally, a few words about Fact’s appearance. Herb Lubalin, voted Art Director of the Year not long ago by the National Society of Art Directors, and the man who art-directed Eros, was given carte blanche in designing Fact. He designed a magazine with large, easy-to-read print, together with an illustration facing every article—a splendid balance of art and text. He also originated the idea of assigning every issue to a different illustrator; using letters-to-the-editor as “fillers” after articles; and have the cover lines read out after the logos, “fact:”. Mr. Lubalin’s design has won the Award of Excellence from the Society of Publication Designers for both 1964 and 1965, and quite as flattering, his design has been imitated piecemeal and wholesale throughout the publishing world.

Warren Boroson

New York, January, 1967

- *The Best of Fact

Thirty-two articles that have made history from America’s most courageous magazine

Edited by Ralph Ginzburg and Warren Boroson

Designed by Herb Lubalin

Avant-Garde Books, New York 1967 - **From the masthead of the first issue of FACT, published on January 1, 1964

Alexander Tochilovsky is the curator of The Herb Lubalin Study Center.

To see the publication in person, please schedule a visit.

An archival project by Mindy Seu (email). Development by Jon Gacnik.

- View metadata from Harvard Hollis

- Download from Harvard Catalog

- The Herb Lubalin Study Center

- Day 43: Fact on Flat File in 100 Days of Lubalin

- Flat File N°1

- Goldwater v. Ginzburg

- Libel in Fact Magazine: Mr. Ginzburg Goes to Jail by John D Mayer Ph.D. for Psychology Today

- Kippenberger and Fact for T, the New York Times Style Magazine by Commercial Type

- Fact Magazine Covers by Nick Sherman

- Ralph Ginzburg’s fact:, Vintage Wikileaks? by Maria Popova

- When Magazines Had Balls by Steven Heller

These issues were scanned by Harvard Library's Imaging Services team. For scanning information, please visit their site.

For more information or edits, please contact Mindy Seu (email).

©1964 Fact Magazine, Inc. All Rights reserved under Berne and Pan-American copyright conventions. Reproduction in whole or part without written permission is strictly prohibited. Trademark “Fact” pending U.S. Patent Office. Printed in the United States of America.